More Information

Submitted: December 18, 2025 | Accepted: December 30, 2025 | Published: December 31, 2025

Citation: Iso T, Elkomos M, Lobsien R, Bahjri K, Malingkas D, Namikawa I, et al. Outpatient Use of Intravenous Furosemide in Patients with Heart Failure. Ann Clin Hypertens. 2025; 9(1): 022-027. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ach.1001041.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ach.1001041

Copyright license: © 2025 Iso T, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Heart failure; Diuretics; Volume overload; Hospital readmission; Intravenous furosemide

Outpatient Use of Intravenous Furosemide in Patients with Heart Failure

Tomona Iso, Mary Elkomos, Ryan Lobsien, Khaled Bahjri, Desiree Malingkas, Isabelle Namikawa and Huyentran N Tran*

Loma Linda University, School of Pharmacy, Loma Linda, California, USA

*Corresponding author: Huyentran N Tran, PharmD, BCCP, BCPS, Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Loma Linda University, School of Pharmacy, Loma Linda, CA, USA, 24745 Stewart Street, Shryock Hall Room 209, Loma Linda, CA, 92350, Email: [email protected]

Introduction: There is limited evidence supporting the use of intravenous (IV) diuretics in the outpatient setting for patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF). In January 2023, our heart failure clinic implemented a protocol to administer IV furosemide for patients presenting with signs of fluid overload during clinic visits. Outpatient IV furosemide may serve as an alternative to hospitalization for ADHF management, potentially reducing the burden on inpatient resources; however, its real-world impact remains unclear. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of outpatient IV furosemide protocol implementation at the clinic level, rather than to assess individual patient-level treatment effectiveness. This study aimed to evaluate whether protocol implementation was associated with changes in ADHF-related hospitalizations and mortality.

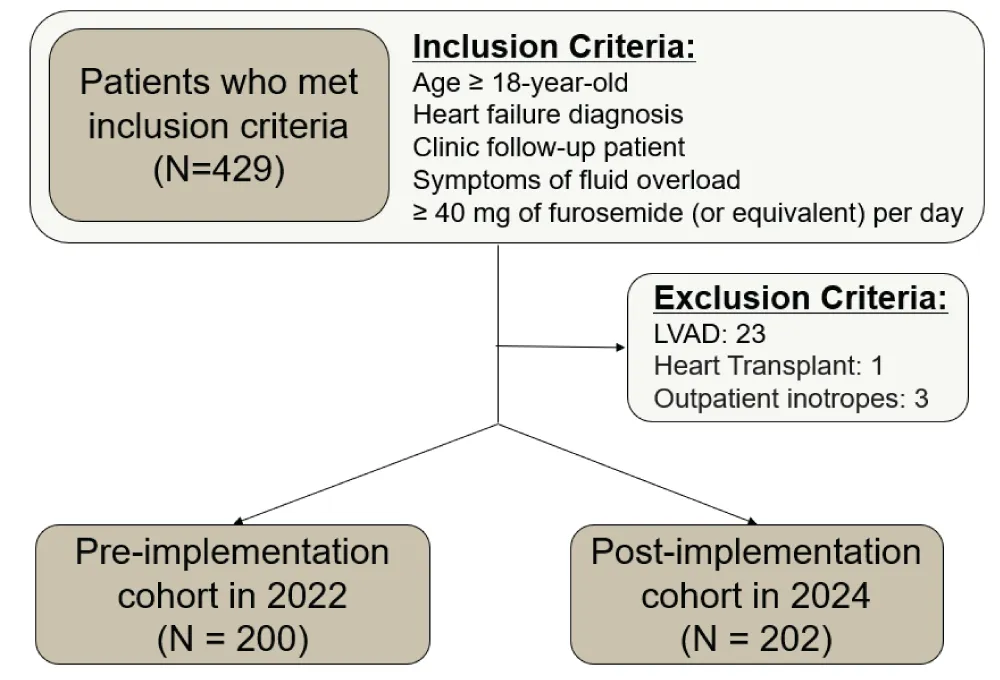

Methodology: This was a single-center, retrospective, pre- and post-implementation study of outpatient IV furosemide included adult heart failure patients followed by the heart failure clinic between 01/01/2022–07/31/2022 (pre-implementation) and 01/01/2024–07/31/2024 (post-implementation). Patients were included if they were receiving loop diuretics (≥ 40 mg oral furosemide or equivalent) and presented with symptoms of fluid overload. Exclusion criteria included a history of heart transplantation, left ventricular assist device insertion, or outpatient inotrope use. The outcomes of the study were the number of hospitalizations and mortality within 30 and 90 days of the clinic visit.

Results: A total of 402 patients were included with 200 patients in the pre-implementation cohort and 202 in the post-implementation group, of whom 14 (7%) received outpatient IV furosemide. At 30 days, ADHF-related hospitalizations occurred in 6% of patients in the pre-implementation cohort and 7.9% in the post-implementation group (p = 0.449), while at 90 days, the proportions were 10% in both groups (p = 0.892). Thirty-day mortality was 1% in both groups (p = 0.994).

Discussion: A higher number of both ADHF-related and all-cause hospitalizations were observed in the post-implementation group. Several factors may explain the limited benefit observed, including a small proportion of post-implementation patients receiving outpatient IV furosemide (7%), baseline differences between groups, and potential residual impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion: The implementation of an outpatient IV furosemide protocol did not result in a significant reduction in heart failure-related hospitalizations or mortality in this study. These findings reflect real-world implementation challenges rather than definitive evidence against outpatient IV diuretics. Further research is needed to evaluate the optimal patient population and timing for outpatient IV diuresis.

Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is a clinical syndrome marked by a sudden worsening of heart failure–related symptoms, commonly due to fluid overload, which leads to frequent hospitalizations and increased mortality among patients with chronic heart failure [1-3]. According to the 2022 ACC/AHA/HFSA guidelines for the management of heart failure, the maintenance use of oral loop diuretics in addition to guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) is recommended for patients with a history of fluid overload, and for patients requiring hospitalization, intravenous (IV) loop diuretics are preferred due to their rapid onset of action and predictable bioavailability [4]. Furthermore, a European consensus paper emphasizes the importance of early management of blood pressure and fluid overload, including the use of IV loop diuretics in prehospital settings [2]. Recognizing the benefits of IV loop diuretics, several studies have investigated their use in outpatient settings, supporting the feasibility and efficacy of outpatient IV diuresis for the management of ADHF with fluid overload [5-12]. A systematic review reported that outpatient IV diuresis was associated with reduced 30-day readmission and mortality rates compared to 2021 Medicare data [8].

Despite encouraging data, there remains limited evidence describing the real-world impact of outpatient IV loop diuretic protocol implementation at the clinic level. In January 2023, our heart failure clinic implemented a new protocol to administer IV furosemide during routine clinic visits for patients presenting with signs of fluid overload. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate whether implementation of an outpatient IV furosemide protocol, compared with usual care prior to implementation, was associated with changes in hospitalization and mortality rates over time.

This was a retrospective, single-center, pre- and post-implementation cohort study conducted at an academic medical center in Southern California. Patients were included if they had a documented ICD-10 diagnosis for heart failure, were followed in the heart failure clinic, were receiving maintenance oral loop diuretics (furosemide ≥40 mg, bumetanide ≥1 mg, or torsemide ≥20 mg), and presented with signs of fluid overload at the time of the clinic visit were included. Fluid overload was defined as the presence of at least one of the following: peripheral edema, resting dyspnea, or jugular venous distension; or at least two of the following: recent weight gain, pulmonary congestion, or abdominal distension. Patients were excluded if they had a history of heart transplantation, left ventricular assist device (LVAD) insertion, or were receiving outpatient inotrope therapy.

The pre-implementation cohort included patients seen between January 1 and July 31, 2022, while the post-implementation cohort included those seen between January 1 and July 31, 2024. If patients were seen in both periods, only the first eligible clinic encounter in the post-implementation period was included in the analysis.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) was defined as a documented prior medical history of myocardial infarction or unstable angina, identified through ICD-10 codes and electronic problem-list documentation, rather than an active ACS event at the time of clinic presentation.

The primary outcome was the number of hospitalizations for ADHF, defined as hospital admission ≥ 24 hours within 30 and 90 days following the clinic visit. The secondary outcomes included 30-day and 90-day all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization. All-cause mortality was defined as death from any cause during the follow-up period, and all-cause hospitalization was defined as any unplanned inpatient admission lasting >24 hours for any indication. These outcomes were identified through a manual review of the electronic health record and were calculated from the date of the index clinic encounter.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board and was granted a waiver of informed consent due to its retrospective design and minimal risk to participants.

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Loma Linda University Medical Center [13,14].

Statistics

Categorical variables were analyzed using χ² (Chi-square) or Fisher’s exact test and reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed with t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, and summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [IQR], respectively. Given the small proportion of patients who received outpatient IV furosemide in the post-implementation cohort, multivariable adjustment or time-to-event analyses were not performed, and results should be interpreted as unadjusted comparisons. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29 (IBM SPSS, Inc., Armonk, NY). A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Overall, a total of 402 patients were included, consisted of 200 patients in the pre-implementation cohort and 202 patients in the post-implementation cohort (Figure 1). Only 14 patients (7%) in the post-implementation group received outpatient IV furosemide during clinic visits.

Figure 1: Flowchart of study population selection and cohort distribution. LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

The baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between the two groups with a few differences (Table 1). A higher proportion of patients in the post-implementation group were receiving sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors compared to the pre-implementation cohort (44% vs. 22%, p < 0.001). Among the four GDMT medications, beta-blockers were the most commonly prescribed at home in both groups. However, 7% in the post-implementation group and 6% in the pre-implementation cohort were not receiving any GDMT medications at the time of the clinic visit, and fewer than 50% of patients in either group were receiving the target dose of GDMT medications.

| Table 1: Baseline Characteristics. | |||

| Pre-implementation cohort (N = 200) | Post-implementation cohort (N = 202) | p value | |

| Female, n (%) | 84 (42%) | 106 (53%) | 0.035* |

| Race, n (%) | 0.073 | ||

| White | 129 (65%) | 144 (71%) | |

| Black or African American | 31 (16%) | 20 (10%) | |

| Other or mixed race | 21 (21%) | 28 (14%) | |

| Asian | 19 (10%) | 10 (5%) | |

| Demographics and physical measures Age (years), mean ± SD |

68.6 ± 14.1 | 68.1 ± 14.2 | 0.703 |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 90.8 (40.9 - 177.7) | 87.2 (43.6 - 248.7) | 0.323 |

| Vital Signs Heart Rate (bpm), mean ± SD |

77.9 ± 15.9 | 77.7 ± 15.2 | 0.449 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg), mean ± SD | 127.5 ± 24.5 | 126.6 ± 21.5 | 0.673 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg), median (IQR) | 72 (38 - 120) | 75 (41 - 128) | 0.048* |

| Cardiac Biomarkers B-Type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) (pg/mL), median (IQR) |

2563 (15.1 - 61066) | 2717 (39 - 70000) | 0.571 |

| Fluid overload symptoms presented at the index clinic visit, n (%) | |||

| Edema | 162 (81%) | 169 (84%) | 0.484 |

| Increased JVP | 86 (43%) | 75 (37%) | 0.23 |

| Weight gain | 65 (33%) | 63 (31%) | 0.778 |

| Shortness of breath | 25 (13%) | 24 (12%) | 0.85 |

| abdominal distension | 14 (7%) | 7 (4%) | 0.111 |

| Pulmonary congestion | 5 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 0.502 |

| Home loop diuretics, n (%) | |||

| Furosemide | 140 (70%) | 124 (61%) | 0.069 |

| Torsemide | 33 (17%) | 46 (23%) | 0.114 |

| Bumetanide | 29 (15%) | 40 (20%) | 0.159 |

| Ethacrynic acid | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.498 |

| HFrEF (LVEF≤40%), n (%) | 88 (44%) | 86 (43%) | 0.773 |

| NYHA functional classification, n (%) | <0.001* | ||

| Class I | 5 (3%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Class II | 18 (9%) | 31 (15%) | |

| Class III | 144 (72%) | 157 (78%) | |

| Class IV | 9 (5%) | 8 (4%) | |

| Data not available | 24 (12%) | 4 (2%) | |

| Home GDMT, n (%) | |||

| Beta-blockers | 158 (79%) | 157 (78%) | 0.756 |

| ACEi/ARB/ARNi | 141 (71%) | 134 (66%) | 0.369 |

| MRA | 62 (31%) | 72 (36%) | 0.323 |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | 43 (22%) | 88 (44%) | <0.001* |

| None | 12 (6%) | 15 (7%) | 0.568 |

| Home GDMT at goal, n (%) | |||

| Beta-blockers | 98 (49%) | 94 (4%) | 0.621 |

| ACEi/ARB/ARNi | 90 (45%) | 94 (47%) | 0.757 |

| MRA | 51 (26%) | 57 (28%) | 0.539 |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | 36 (18%) | 76 (38%) | <0.001* |

| Other home diuretics use, n (%) | |||

| Thiazides | 21 (11%) | 33 (16%) | 0.086 |

| Metolazone | 20 (10%) | 31 (15%) | 0.107 |

| Chlorthalidone | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0.992 |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0.622 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 165 (83%) | 157 (78%) | 0.23 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 94 (47%) | 81 (40%) | 0.163 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 22 (11%) | 7 (4%) | 0.004* |

| None | 5 (3%) | 6 (3%) | 0.773 |

| ACEi: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme inhibitor; ARB: Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker; ARNi: Angiotensin Receptor–Neprilysin inhibitor; GDMT: Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy; HFrEF: Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction; IQR: Interquartile Range; JVP: Jugular Venous Pressure; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; MRA: Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist; NYHA: New York Heart Association; SGLT2: Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Note: Percentages may not sum to 100% due to concurrent use of multiple loop diuretics in some patients. *p - value < 0.05. |

|||

Within 30 days, ADHF-related hospitalization was reported in 12 patients (6%) in the pre-implementation cohort and 16 patients (7.9%) in the post-implementation group (p = 0.449), and within 90 days, 19 patients (10%) in the pre-implementation cohort and 20 patients (10%) in the post-implementation group (p = 0.892) (Table 2). Among them, 5 (3%) in the pre-implementation cohort and 4 (2%) in the post-implementation group were hospitalized on the same day as the clinic visit (p = 0.75). The overall number of hospitalizations numerically increased in the post-implementation group; however, the proportion of hospitalizations due to ADHF within 90 days decreased from 79% (19/24 hospitalizations) in the pre-implementation cohort to 47% (20 out of 43 hospitalizations) in the post-implementation group. Although the overall number of hospitalizations was higher in the post-implementation group, the proportion of ADHF-related hospitalizations among all-cause hospitalizations decreased from 79% (19 of 24 hospitalizations) in the pre-implementation cohort to 47% (20 of 43 hospitalizations) in the post-implementation group.

| Table 2: Primary and secondary outcomes. | |||

| Pre-implementation cohort (N = 200) | Post-implementation cohort (N = 202) |

p - value | |

| Same Day ADHF hospitalization, n (%) | 5 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 0.75 |

| 30-day ADHF hospitalization, n (%) | 12 (6%) | 16 (8%) | 0.449 |

| 90-day ADHF hospitalization, n (%) | 19 (10%) | 20 (10%) | 0.892 |

| 30-day all-cause hospitalization, n (%) | 26 (13%) | 30 (15%) | 0.592 |

| 90-day all-cause hospitalization, n (%) | 24 (12%) | 43 (21%) | 0.012* |

| ADHF: Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. *p < 0.05 | |||

Heart failure-related mortality remained low in both groups. At 30 days, one patient (1%) in each group died (p = 0.994), and at 90 days, two patients (1%) in the pre-implementation cohort and none in the post-implementation group (p = 0.247). For all-cause mortality, 3 patients (2%) in the pre-implementation cohort and 1 patient (1%) in the post-implementation group died within 30 days (p = 0.371), and 7 patients (4%) in the pre-implementation cohort and 2 patients (1%) in the post-implementation group died (p = 0.104) within 90 days.

This retrospective, single-center study evaluated the real-world impact of an outpatient IV furosemide protocol for patients with ADHF. Contrary to our hypothesis, we observed a higher number of ADHF-related and all-cause hospitalizations in the post-implementation cohort. This stands in contrast to previous randomized controlled trials, such as OUTLAST Trial, which reported significantly lower 30-day ADHF hospitalization rates in the IV furosemide group (3.7%) compared to standard care (17.1%) [7].

Importantly, this study was designed to assess the impact of protocol implementation over time rather than the efficacy of outpatient IV furosemide at the individual patient level. Only 7% of patients in the post-implementation cohort received outpatient IV furosemide, which substantially limited the ability to detect patient-level treatment effects.

The lower hospitalization rates observed in our pre-implementation cohort (2022) may reflect lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research has documented significant shifts in healthcare utilization during this period, including altered physical examination practices and restructured diagnostic algorithms [15]. Furthermore, studies have indicated that hospitals maintained higher thresholds for inpatient admission, often only admitting patients with significantly elevated biomarkers or more severe clinical presentations [16]. This pandemic-related suppression of “routine” heart failure hospitalization likely accounts for the observed increase in the post-implementation period as clinical practices and admission thresholds normalized [17].

Baseline differences between groups may have also contributed to outcome variations. More patients in the post-implementation group received SGLT2 inhibitors, which are recommended by clinical practice guidelines for heart failure regardless of left ventricular ejection fraction to reduce morbidity and mortality [4,18,19]. This difference is explained by the timing of guideline updates, where patients in the pre-implementation cohort were seen in early 2022, prior to the publication of the updated heart failure guidelines in April 2022. The use of SGLT2 inhibitors became more common thereafter, likely contributing to greater uptake in the post-implementation group. Conversely, the pre-implementation cohort had a higher incidence of acute coronary syndrome and potentially less severe heart failure symptoms. These differences, along with the small sample of patients who received the intervention, may have diluted any measurable benefit of outpatient IV furosemide.

The imbalance in exposure to outpatient IV furosemide and reliance on unadjusted between-group comparisons represent important limitations and should be considered when interpreting these findings.

The design of this study offers notable strengths. Utilizing a pre- and post-implementation approach allowed for a natural comparison across time in a real-world setting and illustrates the practical application of outpatient IV diuresis protocols within an ambulatory clinical workflow. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. Notably, only 7% of the post-implementation cohort actually received the intended intervention of outpatient IV furosemide. This marked imbalance between the groups substantially reduced the study’s statistical power, as the analysis lacked a sufficient number of treated cases to reliably detect a meaningful clinical difference in outcomes like hospitalization or mortality. As a retrospective study, there was variability in documentation of fluid overload symptoms which might have contributed to reporting bias or underreported clinical events. Furthermore, the 90-day follow-up period may also have been too short to capture longer-term clinical efficacy. Since this study aimed to evaluate the impact of outpatient IV furosemide on ADHF, a pre–post implementation design was used to assess changes in the frequency of ADHF-related hospitalizations. To evaluate if patients would be hospitalized or not, only the first eligible clinic encounter per patient was included in the analysis. However, this methodological decision substantially limited the number of patients who received outpatient IV furosemide (n = 14), which likely diminished the observed effect of the intervention. This contrasts with prior studies, which involved more consistent and frequent administration of outpatient IV diuretics across larger patient populations, possibly contributing to their more favorable outcomes [5-12].

Subgroup analyses may help identify patients most likely to benefit from outpatient IV furosemide for future investigation. Additionally, qualitative studies assessing provider and patient perspectives may reveal logistical or educational gaps that need to be addressed to further enhance the management of ADHF in outpatient settings.

In conclusion, although this study did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of outpatient IV furosemide, it reinforces the feasibility of incorporating outpatient IV diuresis protocols in ambulatory ADHF management. The findings primarily reflect implementation-level outcomes and should not be interpreted as definitive evidence against outpatient IV diuresis. With more robust application and targeted strategies, outpatient IV diuresis may play an increasingly important role in reducing heart failure–related morbidity.

- Arrigo M, Jessup M, Mullens W, Reza N, Shah AM, Sliwa K, et al. Acute heart failure. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):16. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-020-0151-7

- Mebazaa A, Yilmaz MB, Levy P, Ponikowski P, Peacock WF, Laribi S, et al. Recommendations on pre-hospital and early hospital management of acute heart failure: a consensus paper from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, the European Society of Emergency Medicine and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(6):544-558. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.289

- Njoroge JN, Teerlink JR. Pathophysiology and therapeutic approaches to acute decompensated heart failure. Circ Res. 2021;128(10):1468-1486. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.121.318186

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895-e1032. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001063

- Ahmed FZ, Taylor JK, John AV, Khan MA, Zaidi AM, Mamas MA, et al. Ambulatory intravenous furosemide for decompensated heart failure: safe, feasible, and effective. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8(5):3906-3916. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13368

- Buckley LF, Carter DM, Matta L, Cheng JW, Stevens C, Belenkiy RM, et al. Intravenous diuretic therapy for the management of heart failure and volume overload in a multidisciplinary outpatient unit. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(1):1-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2015.06.017

- Hamo CE, Abdelmoneim SS, Han SY, Chandy E, Muntean C, Khan SA, et al. OUTpatient intravenous LASix trial in reducing hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure (OUTLAST). PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0253014. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253014

- Kalkur RS, Hintz JP, Pathangey G, Manning KA. Safety and efficacy of outpatient intravenous diuresis in decompensated heart failure: a systematic review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1481513. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1481513

- Nair N, Ray N, Pachariyanon P, Burden R, Skeen N. Impact of outpatient diuretic infusion therapy on healthcare cost and readmissions. Int J Heart Fail. 2022;4(1):29-41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.36628/ijhf.2021.0031

- Ryder M, Murphy NF, McCaffrey D, O’Loughlin C, Ledwidge M, McDonald K. Outpatient intravenous diuretic therapy: potential for marked reduction in hospitalisations for acute decompensated heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(3):267-272. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.01.003

- Verma V, Zhang M, Bell M, Tarolli K, Donalson E, Vaughn J, et al. Outpatient intravenous diuretic clinic: an effective strategy for management of volume overload and reducing immediate hospital admissions. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13(4):245-251. Available from: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr4499

- Wierda E, van Maarschalkerwaart WWA, van Seumeren E, Dickhoff C, Montanus I, de Boer D, et al. Outpatient treatment of worsening heart failure with intravenous diuretics: first results from a multicentre 2-year experience. ESC Heart Fail. 2023;10(1):594-600. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.14168

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Palazzuoli A, Metra M, Collins SP, Adamo M, Ambrosy AP, Antohi LE, et al. Heart failure during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical, diagnostic, management, and organizational dilemmas. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9(6):3713-3736. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.14118

- Mishra T, Patel DA, Awadelkarim A, Sharma A, Patel N, Yadav N, et al. A national perspective on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on heart failure hospitalizations in the United States. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48(9):101749. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.101749

- Shoaib A, Van Spall HGC, Wu J, Cleland JGF, McDonagh TA, Rashid M, et al. Substantial decline in hospital admissions for heart failure accompanied by increased community mortality during COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2021;7(4):378-387. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcab040

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2023 focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(37):3627-3639. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad195

- Kittleson MM, Panjrath GS, Amancherla K, Davis LL, Deswal A, Dixon DL, et al. 2023 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(18):1835-1878. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.393